Knik Tribe's History.

Chief Visilla (Wasilla)

The City of Wasilla was named after Chief Visilla. He was born soon after the smallpox epidemic that decimated 50 percent of the Upper Cook Inlet Athabascan population in the mid-1800s. As a young man he witnessed many changes starting with Russia's sale of Alaska in 1867 to the United States. Visilla, known to write in Cyrillic was able to grow in prominence during the American fur trade. He Became the Qesh'qa or Bente'en, Chief of Benteh (among the lakes) a village situated in the vicinity of Wasilla and Cottonwood Lakes.

Chief Visilla reportedly brokered peace with the Copper River Ahtna who on occasion traversed the Matanuska River to plunder, raid and kidnap women and children from Dena'ina villages, including those of the chief. After chasing, killing and confronting the perpetrators, his heroism helped to distinguish him. In addition to acquiring trade items, he provided well for his people, overseeing the harvesting of animals, fish and plants to sustain them during winter months. Known to be a generous man he "adopted many children" and took good care of them. He was well-known as a healer and shaman, in addition to the forger of peace.

Upon his death in 1907, the Seward Gateway reported:

...he became chief through his mental and moral superiority and ruled the other natives sternly. Because of his character and intelligence he was held in much esteem by white men who knew him.

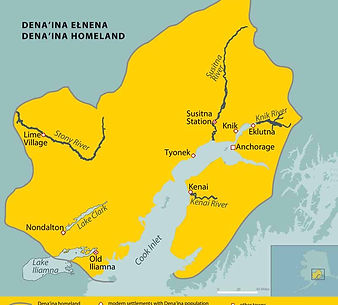

The Dena'ina Athabascan people are the indigenous people of Tikatinu (Cook Inlet) and southwestern Alaska. There are four distinct dialects of Dena'ina: Upper Tikahtnu, Outer Tikahtnu, Lakes region, and Interior (middle Kuskokwim; near the Stony River). The lands and waters of Upper Tikahtnu: Anchorage, Eklutna, Knik, Wasilla, Palmer, Girdwood, and Chickaloon fall within Dena’ina Etnena (Qena'ne Country). Specifically, it is home to the Kenaht’ana, the indigenous people of Nuti (Knik Arm), who today are members of Eklutna (Idlughet) and Knik (K'enakatnu) Tribes. Following the recession of the glaciers in Tikahtnu, a large valley was created and fed by many rivers. The Matanuska and Knik Rivers today come together at their confluence with Knik Arm; however, it is probable that at one time they joined as one river, discharging into Tikahtnu at the strait between Anchorage and Point MacKenzie. Subsequent earthquakes, landslides, flooding, and erosion have widened the channel between the two points, creating Knik Arm.

Before contact, the Dena'ina people, like all peoples in Alaska, were self-sufficient, living in communal hunter-gatherer villages. The Dena'ina cultures in Alaska were especially thriving and expanding with every generation up until first contact with Western culture. That happened when the British, in 1778, Captain James Cook's Expedition reached the shores of Tikahtnu, which now bears his name: Cook Inlet. Shortly thereafter, Russian trading companies established the first posts on the Kenai Peninsula, Kasilof (Fort St. George) in 1787, and Kenai (Fort St. Nicholas) in 1791.

The Dena'ina trappers, traders, and guides were invaluable during the Russian fur trade. Most trade funneled through Dena'ina traders, enabling most Dena'ina communities to remain largely independent from direct Russian control and influence for a short time at least. The most influential aspect of Western culture has become an enduring part of many Dena'ina lifestyles today. The Russian traders also brought many new items to Alaska and Tikahtnu, such as sugar, tea, salt, flour, foods, and alcohol. The traders also brought technology, such as guns, medicines, metal tools, and writing. Worst of all, these invaders brought diseases; one example of this was a smallpox epidemic from 1895 to 1845, in which at least half the Dena'ina population perished. Another consequence of population loss and the influx of Western medicine created a willingness to convert to Christianity, following the establishment in 1845 of the Russian Orthodox Church in Kenai. Over the next several decades, priests traveled to visiting Dena'ina villages. And gradually most Dena'ina became followers of Orthodox Christianity, blending traditional Dena'ina spirituality and Russian Orthodox traditions. In the 1880s, the Russian missionaries completed a census and reported a total of 142 Dena'ina Athabascans in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley (Peter, Louise, Early days in Wasilla), after only 100 years of contact with Western culture.

The Russians tried many different business ventures including coal, copper and other mineral exploration, but none was as successful as the fur trade. After hunting sea-otters and fur seals to almost extinction, the Russians, thinking there was no other economic benefits in Alaska sold their trading interests to the United States in 1867, before the English usurped the Russian claim in Alaska.

The discovery of gold in Alaska brought a new breed of Euro-Americans and along with these new Americans, came new technologies and new diseases. The Dena'ina population was greatly reduced during this time, due to the influx of new diseases. During the gold rush era, the Dena'ina had been involved with Western culture for at least 100 years. They were familiar with trading with foreigners and Western culture and technology. The Dena'ina culture adapted but still maintained traditional hunting and fishing methods, while using current technology. The Dena'ina at this time continued to trap and trade, but some held jobs, became guides, or entrepreneurs.

In 1915, the federal government started to build a railroad that cut straight through the Dena'ina territory into the interior of Alaska. Anchorage was selected as the headquarters. Many Dena'ina helped build the railroad, especially during the time between World War I and World War II. In 1918, a large influx of railroad workers brought with them a fatal influenza epidemic. This epidemic hit Southcentral Alaska especially hard, and as a result, almost fifty percent (50%) of the Dena'ina people perished in a short period of time; the second viral epidemic to devastate the Dena'ina.

The Dena'ina that survived slowly became engulfed and expropriated by an ever-increasing number of settlers. Following the “founding” of Anchorage in 1975, and with the two military installations built during World War II, public and private development, the dwindling Dena'ina became enveloped in modern Western culture.

During and following the war years, the Dena'ina lost most of their traditional hunting and fishing areas and were denied their subsistence hunting and fishing rights by the State of Alaska. Traditional use areas were turned into homesteads, agricultural areas; or were cut by railroads and highways. The Dena'ina Tikahtnu territory became predominantly non-native. The Dena'ina lost important subsistence gathering places, but they still practiced their traditional and cultural customs of harvesting land and gathering resources. With Alaska becoming a state in 1959, the Dena'ina had to conform and abide by state laws and regulations. Some, not having subsistence fishing rights, became commercial fishermen for their needs. The Tikahtnu Dena'ina soon felt like strangers in their own territory. They had lost all of their traditional use areas to explosive development radiating from the newly established town of Anchorage.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA), two Upper Tikahtnu Dena'ina tribes were recognized; Knik Tribal Council (KTC) was formally recognized as a tribe in 1989, and in 1982 the Native Village of Eklutna (NVE) became formally recognized. With the passing of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971, the State of Alaska conveyed lands to the Dena’ina who were forced to form a regional native corporation: Cook Inlet Region, Incorporated (CIRI), and two village corporations; Knikatnu, Inc. and Eklutna, Inc.. The Dena'ina lost approximately 98% of their traditional use areas, but they received close to 22,000 acres based on economic value and not necessarily on traditional use areas. Although the Dena'ina are land owners, they must now comply with state and federal hunting and fishing regulations. The tribal governments must now apply for educational and ceremonial harvesting permits to hunt and fish. Since time immemorial, the Dena'ina have lived in harmony within these traditional territories, now as federally recognized tribes, tribal members have no sovereignty to practice traditional lifestyles.

ANCSA created a corporate structure that was formed to manage tribal allocated land to be used by all indigenous people in Alaska. The Dena'ina of Upper Tikahtnu have some governmental authority as federally recognized tribes, but no land or population base to assert that authority. As of 2010, there were approximately 90 Dena'ina descendants enrolled in Knik Tribal Council, and a little over 300 enrolled in the Native Village of Eklutna.

The Knik Tribal Council (KTC) is a federally recognized tribal government founded by 28 original members who voted to establish the council and its mission of service. Comprising of over 1,500 tribal citizens, Knik Tribe (KT) has grown into a thriving organization, employing over 100 individuals and providing millions of dollars in essential services to its tribal members and all other Native Americans and Alaska Natives within its service area. The tribal government includes the following departments: Housing/Community Services Department, Tribal Development Department, Finance Department, Information Technology Department, and Administration Department. Knik Tribe serves the six thousand Alaska Natives or Native Americans living within the Knik service area.

History

of the Dena'ina

Athabascans

What the Salmon Means to the Dena’ina People.

Eggs: hatch in 2 months

Alevin: feed of yolk-sac for several weeks

Fry: 5 to 10 weeks old and swimming

Parr: several months old, develops ‘finger’ markings

Smolt: 1-3 years old, will group and head out to sea

Adult: spends 1 to 8 years at sea

Spawning Adults: spawn and die within 2 weeks

Services

Fry

Services

Parr

Services

Smolt

Services

Adult

Traditional Territory

As the Dena'ina adapted to this land, their numerous house-pits, cache-pits and remains of campsites have characterized the landscape as Dena'ina territory. They established villages, hunting and fishing camps, gathering sites, and trails. They defended their territory against Yup'k, Sugpiag, Russian, and Euro-American encroachment. As a whole, the Dena'ina collective territory equaled in size to the state of Wisconsin. Within their territory, tribes, clans, and families had separate use areas. Every tributary draining into Tikahtnu was considered Dena'ina territory. The Dena'ina made use of all the waterways from the headwaters to the mouth of every inlet, bay, river, creek, stream, and lake.

The traditional lifestyle of the Dena'ina was to be one with the environment; they were the dominant species, but spiritually they were part of the environment and equal with the animals who call the Dena'ina Qutsidghe’i’ina “Campfire People” (Kalifornsky, Peter. A Dena'ina Legacy: The Collected Writings of Peter Kalifornsky). The Dena'ina created and adhered to a form of government with laws, punishment, structured society, spiritual practices, medicines, food, shelter, hunting, fishing, gathering, and harvesting technology.

Dena'ina spirituality believed that every plant and animal within their ecosystem or environment served a purpose, and each had a spirit that, if harmed or disrespected, would come back for revenge. The Dena'ina maintained their ecosystem so that all resources would coexist in a way that would ensure balance and continuation of their lifestyle and relationship with the land, water, plants, and animals. Every resource was respected and utilized fully with no waste or over-harvesting. The Dena'ina were a populous, thriving people with a rich culture at the time of first contact.

Different Species and Ways of Processing

Five species of salmon spawn in the drainage systems of Knik Arm. King Salmon (Chinook) run in Ship Creek and Campbell Creek (in the present day Anchorage area) and in the Matanuska River, predominantly in May and June. Runs of red (sockeye), chums (dog), pinks (humpback), and silvers (coho) follow during the summer. Silvers are the last to appear, arriving first in July but running well into September. Salmon have historically spawned in many drainage systems of Knik Arm, including those of the Eagle River, Eklutna River, Knick River, Matanuska River, Wasilla Creek, Cottonwood Creek, and Fish Creek.

Most salmon were preserved by drying and smoking and stored in caches for use during the lean winter months. Baba (dry fish) and balik (smoked strips of salted salmon) are familiar products among the Dena'ina today. In addition, numerous other methods of putting up fish might be employed. For example, fish might be buried in the ground in birch bark baskets to make chugilin ("fermented fish"). These supplies of food were shared among household members and their kin.

Liq’aka’a N’u (King Salmon Month)

Of all the diverse resources available to the Knik Arm Dena'ina, the most important has been the salmon. June is known as Liq'aka'a Nu ('king salmon month'). King salmon are especially significant because of their early arrival and large size. Since the best runs of this fish occurred in the present-day Anchorage area, Knik Arm Dena'ina from further up the Arm traveled to traditional fishing sites there in May and June. A major means for catching king salmon were tanik’edi (figure 1), platforms made of wooden pikes which extended into the water at the mouths of salmon streams. Individuals stood on these platforms and dip-netted fish. During the remainder of the summer (June, July, August), runs of other salmon species, especially reds and silvers, were utilized. Fish traps and weirs were constructed on such streams as Fish Creek, Wasilla Creek, and Cottonwood Creek, and at the mouths of many lakes, such as Big Lake and Lucile Lake. Village leaders (geshga) supervised salmon harvests and regulated the distribution of the catch.

In June, when king salmon runs begin in the lower Knik Arm, camps were established along Chester Creek, Ship Creek, at Points Campbell and Woronzof, and in the present-day Fort Richardson area. As the city of Anchorage grew, and as land was withdrawn for military bases, the people of Knik and Eklutna could no longer use these sites. The Indians relocated their camps on Fire Island and Point Possession, where they were separated from the Anchorage area by stretches of dangerous water. Later in the summer, Knik Indians fished at Fish Creek and other Knik Arm tributaries. Fish traps were still used early in this century; gill nets later replaced them. The Knik Arm Dena'ina sold a portion of their catch to miners, city dwellers, and canneries.

Summary

Evidence in some old stories indicates that local scarcities and starvation could occur in late winter. If stored supplies did run low, village leaders organized more extensive hunting and trading expeditions. This relatively difficult season ended with the return of waterfowl, eulachon, and salmon in spring, when the annual cycle began anew.

In conclusion, the members of the communities of Knik and Eklutna have traditionally and historically utilized a territory in the midst of one of Alaska’s most dynamic regions. Extraordinary pressures have been placed on local fish and game populations and on the people whose group identity has depended upon the use of these resources. Despite economic change, human population growth, loss of fishing sites and hunting territories, and in recent years, governmental regulations, wild resources continue to be economically, nutritionally, and culturally valuable to the Dena'ina communities of Knik Arm.

Alevin

Eggs

Salmon Lifecycle

mouseover

Spawning

Adult

The Steps:

*Prepare the nets

*Set the nets

*Process the Salmon

Enjoy!

Benqda — Dena'ina for Lake Lucille

Situated in South Central Alaska, Upper Cook Inlet has provided an abundance of subsistence resources for Dena’ina Athabascans to harvest from land and water. They were hunters, trappers, and fishermen. The outlet of Benkda (no good lake) with Tutik’ełtuni Betnu (creek that extends down) was a popular fishing spot for the Theodore family where large salmon and trout were caught. According to Bailey Theodore, his great-great-grandfather bought Benkda Lake for the Nulchina (his people, the sky clan) to fish. Theodore understood the lake was purchased with K’enq’ena (dentalia beads).

Fish Traps

Using a trap made of willows enabled the Dena’ina to catch migrating muskrat in addition to fish. Fish traps could be as big as 4 feet wide and 8 feet long. When they were filled with fish, the Dena’ina would roll the traps out of the water and onto land for harvesting. Smokehouses lined the banks of a creek and were filled with harvested fish in preparation for winter.

Dena'ina Today

The Dena’ina culture is alive today through fish camps, artwork, dance, and potlatches. Subsistence food gathering continues to be a vital part of a Native family’s diet.

Today

Along water bodies between Lake Lucille and Big Lake to the west, archaeologists have found evidence of food caches, overnight shelters, canoe slips and Dena’ina houses. Summer and winter trails were created for different seasons. Ice across and over water bodies created a preferred route in winter and waterways were popular conduits in summer. Numerous trails led to popular hunting and gathering areas. Although fish was the mainstay of their diet, the Dena’ina gathered a variety of plants.

Contact Us

Email: info@kniktribe.org

Tel: 907-373-7991

ICWA Fax: 907-373-2153

Main Fax: 907-373-2178

Admin Fax: 907-373-2161

Physical Address

1744 North Prospect

Palmer, AK 99645

Mailing Address

PO Box 871565

Wasilla, AK 99687